Wireless

L4S in Wi-Fi: A Path to Seamless Interactive Experiences

Key Points

- Broadband service providers are beginning to implement L4S functionality in their networks. The technology enables applications to achieve low latency and high efficiency, ultimately helping deliver enhanced and more reliable user experiences.

- CableLabs worked with the Wireless Broadband Alliance to develop a set of guidelines for equipment suppliers to use when implementing L4S in their Wi-Fi products.

- Wi-Fi networks are frequently a point of congestion in end-to-end networks, creating a need for L4S support in those networks.

Modern networks deliver impressive speeds — often reaching gigabits per second — yet they still suffer from unpredictable delays that can disrupt interactive applications. Whether it’s video conferencing, cloud gaming or remote collaboration, these inconsistencies can lead to frustrating user experiences. As network operators strive to enhance reliability and responsiveness, a more effective solution is needed.

To address this need, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) — an organization responsible for developing open internet standards — has specified the Low Latency, Low Loss, and Scalable (L4S) throughput architecture. L4S enables applications to implement a new mechanism to ensure that they are sending their data as fast as the network can support, but no faster. The result is efficient capacity usage with minimal queuing delay and low packet loss.

This shift to a more comprehensive quality of service (QoS) model is essential for delivering smooth and uninterrupted performance across a wide range of services, from gaming and video streaming to cloud computing and augmented reality.

What Is L4S?

The power of L4S stems from new congestion control algorithms that adapt to new fine-grain notifications of congestion at the IP layer across various network elements along an end-to-end (E2E) path. While L4S can be deployed on each element of the network, its most significant impact is at points of congestion, also referred to as network bottlenecks — where the rate of incoming packets can exceed the departure rate.

The cable industry already adopted support for L4S, as part of the Low Latency DOCSIS® 3.1 specifications (and it carries forward into DOCSIS 4.0 gear as well). Operators are beginning to enable this functionality in their networks, and more are expected to do so over the coming months. That said, the broadband access network segment is only one potential bottleneck. There are others on the E2E path.

The Need for L4S in Wi-Fi Networks

Wi-Fi networks, in particular, require L4S support as they are frequently a point of congestion in E2E networks. Indeed, although Wi-Fi networks often advertise their maximum capacity that is greater than the broadband access connection, actual performance is significantly influenced by factors such as the distance between clients and the access point (AP), as well as the number of APs and clients operating on the same channel. This need for L4S support is even more critical given that a substantial portion of internet traffic is transmitted over Wi-Fi.

WBA L4S Implementation Guidelines and NS3 Simulator

Wi-Fi presents unique challenges for L4S implementation compared to wired technologies such as DOCSIS® networks. While wired networks primarily see only buffering delays, Wi-Fi additionally introduces media access delays, which can be significant in congested environments. To tackle these challenges, CableLabs worked within the End-to-End QoS Working Group of the Wireless Broadband Alliance (WBA) to produce a set of guidelines to implement L4S in current Wi-Fi products.

The guidelines cover:

- An overview of L4S technology, explaining its mechanics and benefits.

- The importance of L4S support in Wi-Fi equipment for improving E2E application performance.

- Implementation strategies for Wi-Fi equipment suppliers to enable L4S functionality in their products.

- Simulation and test results demonstrating the advantages of L4S in real-world scenarios

The simulation results are based on a Wi-Fi NS3 model developed by CableLabs, designed to evaluate L4S performance in Wi-Fi networks. The model is open-source and available to industry and research players to support L4S deployment and assess its impact on various use cases. In addition, CableLabs provided field test data that were conducted with a Nokia AP.

The Future of L4S in Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi equipment suppliers today can leverage the L4S Implementation Guidelines to develop support on their existing platforms (e.g. Wi-Fi 7 devices). Several proposals from industry leaders, including CableLabs, aim to incorporate L4S support into the 802.11 Wi-Fi standard, ensuring native support for L4S across future Wi-Fi generations.

In addition, as the ecosystem matures, CableLabs will continue refining the NS3 model to expand its applicability to more scenarios and use cases. This ongoing effort is being advanced in collaboration with the WBA E2E QoS working group.

L4S is a critically important next step in the evolution of the internet that solves many of the issues that cause frustrations today, where it seems that bandwidth alone hasn’t fully enabled reliable and responsive interactive application experiences.

To fully take that step, the segments of the network that are the likely bottlenecks in residential deployments — the access network and the Wi-Fi segment — both need built-in support for L4S.

10G

L4S Technology: A New Congestion-Control Solution for Latency

In a digital world where every second counts, technologies that enable smooth, efficient transmission of data are paramount to ensuring the quality of our online experiences. Reliable connectivity is a must, and the need for it grows exponentially more essential every day, particularly as more applications harness the power of 10G.

The 10G platform is a game-changing, multigigabit network made possible by DOCSIS technologies. It will deliver faster speeds, enhanced reliability, better security and lower latency. Low latency is especially critical for real-time communication applications because it helps create user experiences that are free of delay and disruption.

Many of the applications that we use every day weren’t designed with low latency in mind, and they actually cause network congestion that can disrupt our real-time communications. That’s why we need solutions that can relieve networks of this congestion by combating latency, jitter and packet loss. Low Latency, Low Loss, Scalable Throughput (L4S) technology is a part of that solution.

What Causes Network Congestion and Latency?

It’s important to understand the source of network congestion and the reason for it. Although it’s well known that latency increases when congestion increases, what’s less commonly known is why it happens. Contrary to what many people think, it’s not the result of too much traffic and too little available bandwidth.

In reality, most of the applications we use every day use congestion control. What that means is that applications are constantly adjusting their sending rates, aiming to send as fast as they can and backing off only when they detect congestion. But congestion-control mechanisms that applications use haven’t evolved significantly since the early days of the internet in the mid-1980s. Those algorithms, such as TCP Reno and CUBIC, rely on the network to provide deep packet buffers and then drop packets when the buffers overflow. The algorithm ramps up, causes delay and packet loss, backs off and ramps up again. As a result, those mechanisms can introduce latency, jitter (also known as latency variation) and packet loss — not only to themselves but also to other applications using the network at the same time.

What Is L4S?

L4S is a core component of the Low Latency DOCSIS specifications, which many other networking technologies are also adopting. It enables a new congestion-control mechanism for capacity-seeking applications wanting to optimize their sending rate, while dramatically reducing network latency, jitter and packet loss.

L4S is ideal for applications that are optimized by high data rates, consistent ultra-low latency and near-zero packet loss — including cloud gaming and virtual reality/augmented reality (VR/AR) applications and high-quality video conferencing. L4S is also beneficial for other applications that are latency-bound, such as general HTTP traffic.

How Does L4S Work?

The end-to-end L4S solution provides high-fidelity congestion feedback from the network bottlenecks to the applications being used. The process involves applications implementing a new congestion-control algorithm that can understand that feedback, adjust their sending rates with better precision and fully utilize link capacity without causing latency and packet loss.

The L4S mechanism can be used by any application, such as TCP or QUIC, as well as real-time applications that use UDP or RTP.

A standardized solution defined by the Internet Engineering Task Force, L4S has already been adopted by cable broadband networks and is supported in the DOCSIS cable modem protocol. Work is underway to implement it in 5G and Wi-Fi networks.

I delve much deeper into L4S in the video below. Watch to learn more about how it's being implemented, the results of recent testing and performance findings, and more.

10G

L4S Interop Lays Groundwork for 10G Metaverse

What does the future look like to you? Your vision could very well be dependent on L4S—Low Latency, Low Loss, Scalable Throughput—technology. A key component of the Low Latency DOCSIS® specifications, L4S is fundamental to the cable industry’s 10G initiative and underpins three of the four tenets of the multi-gigabit platform: speed, low latency and reliability. By allowing applications to fully make use of multi-gigabit connections and, in the process, achieve ultra-low latency and near-zero packet loss, L4S will change what's possible in broadband networks.

The technology will enable the interactive and immersive media experiences of the future—metaverse types of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) applications that once were only a figment of science-fiction imagination. L4S can also make possible applications that haven’t been envisioned yet! And now, we’re a step closer to deploying this critical technology after an interoperability event that drew participants from organizations including Apple, Google, Meta, NetApp, Netflix, Nokia and NVIDIA, as well as cable industry orgs Casa Systems, Charter Communications, Comcast and CommScope.

Low Latency DOCSIS Specs and IETF Standards

CableLabs and Kyrio, with support from Comcast, Apple and Google, organized the Interop event—the first in the world to test implementations of L4S. As an early adopter, promoter and contributor to the development of the technology, CableLabs has positioned the cable broadband industry to take the lead in capitalizing on this transformational change in the way applications interact with the internet. CableLabs integrated support for L4S into its Low Latency DOCSIS specifications from the beginning and has been a leader in pushing for its standardization in the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF).

Engineers participate in the L4S Interop in July.

Broad Range of Participants

The four-day Interop event, held in coordination with the IETF during the organization’s “Hackathon” in late July in Philadelphia, drew 32 engineers from 15 organizations. The engineers tested and refined their applications on Low Latency DOCSIS gear, including cable modems using Systems-on-a-Chip (SoCs) from multiple suppliers and cable modem termination system (CMTS) equipment from Casa Systems and CommScope. In addition, two L4S-enabled Wi-Fi access points—one from Nokia and the other from Google Nest—participated, and Nokia brought a 5G network emulator.

The goal of the event was to allow engineers to test and refine their implementations, rather than to demonstrate the capabilities of the technology. But we did manage to publish some impressive early benchmark results and demonstrate some of the applications nonetheless. In the first public demonstration of Apple’s QUIC-Prague L4S congestion control design (recently announced at WWDC 2022) running over a Low Latency DOCSIS connection, the implementation achieved up to 50x reduction in latency and jitter and 70x reduction in packet loss. On the application front, NVIDIA demonstrated the L4S-enabled version of its GeForce Now cloud gaming service, and Nokia demonstrated a telepresence application that allows a user to use a touch screen to remotely control the live view generated by a 360° camera.

Continuing the Momentum

This was an important and successful first event for the cable industry and the internet, but we’ve only just begun. CableLabs and Kyrio plan to host a follow-up event at our Louisville, Colorado, headquarters in October, and we plan to facilitate another event in London in November. We welcome CableLabs members, cable vendors, application developers and other L4S implementers to join us at these upcoming events as we continue to advance in our march toward 10G. To register for the October L4S Interop, click the button below.

In addition, Kyrio provides a service for application developers who wish to test their 10G L4S applications using Low Latency DOCSIS network gear—privately, on their own time and at their own pace. If you’re interested in Kyrio’s testing services, learn more or contact the team here.

DOCSIS

CableLabs Releases DOCSIS® Simulation Model

When it comes to technology innovation, one of the most powerful tools in an engineer’s toolbox is the ability to rapidly test hypotheses through simulations. Simulation frameworks are used in nearly all engineering disciplines as a way to understand complex system behaviors that would be difficult to predict analytically. Simulations also allow the researcher to control variables, explore a wide range of conditions and look deeply into emergent behaviors in ways that are either impossible or extremely challenging to accomplish in real-world testbeds or prototype implementations.

For some of our innovations, CableLabs uses the “ns” family of discrete-event network simulators (widely used in academic networking research) to investigate sophisticated techniques for making substantial improvements in broadband network performance. The ns family originated at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the mid-1990s, and has evolved over three versions, with “ns-3” being the current iteration that is actively developed and maintained. The open-source ns-3 is managed by a consortium of academic and industry members, of which CableLabs is a member. Examples of features developed with the help of ns include the Active Queue Management feature of the DOCSIS 3.1 specifications, which was developed by CableLabs using ns-2, and more recently, the Low Latency DOCSIS technology, which was created using models that we built in ns-3. In both cases, the simulation models were used to explore technology options and guide our decision making. In the end, these models were able to predict system behavior accurately enough to be used as the reference against which cable modems are compared to assess implementation compliance.

As a contribution to the global networking research community, CableLabs recently published its DOCSIS simulation model on the ns-3 “App Store,” thus enabling academic and industry researchers to easily include cable broadband links in their network simulations. This is expected to greatly enhance the ability of DOCSIS equipment vendors, operators and academic researchers to explore “what-if” scenarios for improvements in the core technology that underpins many of the services being delivered by cable operators worldwide. For example, a vCMTS developer could easily plug in an experimental new scheduler design and investigate its performance using high-fidelity simulations of real application traffic mixes. Because this DOCSIS model is open source, anyone can modify it for their own purposes and contribute enhancements that can then be published to the community.

As a contribution to the global networking research community, CableLabs recently published its DOCSIS simulation model on the ns-3 “App Store,” thus enabling academic and industry researchers to easily include cable broadband links in their network simulations. This is expected to greatly enhance the ability of DOCSIS equipment vendors, operators and academic researchers to explore “what-if” scenarios for improvements in the core technology that underpins many of the services being delivered by cable operators worldwide. For example, a vCMTS developer could easily plug in an experimental new scheduler design and investigate its performance using high-fidelity simulations of real application traffic mixes. Because this DOCSIS model is open source, anyone can modify it for their own purposes and contribute enhancements that can then be published to the community.

If you’ve ever been interested in exploring DOCSIS performance in a particular scenario, or if you have had an idea about a new feature or capability to improve the way data is forwarded in the network, have a look at the new DOCSIS ns-3 module and let us know what you think!

10G

CableLabs Low Latency DOCSIS® Technology Launches 10G Broadband into a New Era of Rapid Communication

Remember the last time you waited (and waited) for a page to load? Or when you “died” on a virtual battlefield because your connection couldn’t catch up with your heroic ambitions? Many internet users chalk those moments up to insufficient bandwidth, not realizing that latency is to blame. Bandwidth and latency are two very different things and adding more bandwidth won’t fix the internet lag problem for latency-sensitive applications. Let’s take a closer look at the difference:

- Bandwidth (sometimes referred to as throughput or speed) is the amount of data that can be delivered across a network over a period of time (Mbps or Gbps). It is very important, particularly when your application is trying to send or receive a lot of data. For example, when you’re streaming a video, downloading music, syncing shared files, uploading videos or downloading system updates, your applications are using a lot of bandwidth.

- Latency is the time that it takes for a “packet” of data to be sent from the sender to the receiver and for a response to come back to the sender. For example, when you are playing an online game, your device sends packets to the game server to update the global game state based on your actions, and it receives update packets from the game server that reflect the current state of all the other players. The round-trip time (measured in milliseconds) between your device and the server is sometimes referred to as “ping time.” The faster it is, the lower the latency, and the better the experience.

Latency-Sensitive applications

Interactive applications, where real-time responsiveness is required, can be more sensitive to latency than bandwidth. These applications really stand to benefit from technology that can deliver consistent low latency.

As we’ve alluded, one good example is online gaming. In a recent survey we conducted with power users within the gaming community, network latency continually came up as one of the top issues. That’s because coordinating the actions of players in different network locations is very difficult if you have “laggy” connections. The emergence of Cloud gaming makes this even more important because even the responsiveness of local game controller actions depends on a full round-trip across the network.

Queue Building or Not?

When multiple applications share the broadband connection of one household (e.g. several users performing different activities at the same time), each of those applications can have an impact on the performance of the others. They all share the total bandwidth of the connection, and they can all inflate the latency of the connection.

It turns out that applications that want to send a lot of data all at once do a reasonably good job of sharing the bandwidth in a fair manner, but they actually cause latency in the network when they do it, because they send data too quickly and expect the network to queue it up. We call these “queue-building” applications. Examples are video streaming and large downloads, and they are designed to work this way. There are also plenty of other applications that aren’t trying to send a lot of data all at once, and so don’t cause latency. We call these “non-queue-building” applications. Interactive applications like online gaming and voice connections work this way.

The queue-building applications, like video streaming or downloading apps, get best performance when the broadband connection allows them to send their data in big bursts, storing that data in a buffer as it is being delivered. These applications benefit from the substantial upgrades the cable industry has made to its networks already, which are now gigabit-ready. These applications are also latency-tolerant – user experiences are generally not impacted by latency.

Non-queue-building applications like online gaming, on the other hand, get the best performance when their packets don’t have to sit and wait in a big buffer along with the queue-building applications. That’s where Low Latency DOCSIS comes in.

What is Low Latency DOCSIS 3.1 and how does it work?

The latest generation of DOCSIS that has been deployed in the field—DOCSIS 3.1—experiences typical latency performance of around 10 milliseconds on the access network link. However, under heavy load, the link can experience delay spikes of 100 milliseconds or more.

Low Latency DOCSIS (LLD) technology is a set of new features, developed by CableLabs, for DOCSIS 3.1 (and future) equipment. LLD can provide consistent low latency (as low as 1 millisecond) on the access network for the applications that need it. The user experience will be more consistent with much smaller delay variation.

In LLD, the non-queue-building applications (the ones that aren’t causing latency) can take a different path through the DOCSIS network and not get hung up behind the queue-building applications. This mechanism doesn’t interfere with the way that applications go about sharing the total bandwidth of the connection. Nor does this reduce one application's latency at the expense of others. It is not a zero-sum game; rather, it is just a way of making the internet experience better for all applications.

So, LLD gives both types of applications what they want and optimizes the performance of both. Any application that wants to be able to send big bursts of data can use the default “classic” service, and any application that can ensure that it isn’t causing queue build-up and latency can identify its packets so they use the “low latency” service. Both then share the bandwidth of the broadband connection without one getting preference over the other.

Incorporating LLD Technology

Deploying Low Latency DOCSIS in a cable operator’s network can be accomplished by field-upgrading existing DOCSIS 3.1 CMs and CMTSs with new software. Some of the low latency features are even available to customers with older (pre-DOCSIS 3.1) CMs.

The technology includes tools that enable automatic provisioning of these new services, and it also introduces new tools to report statistics of latency performance to the operator.

Next Steps

DOCSIS equipment manufacturers are beginning to develop and integrate LLD features into software updates for CMTSs and CMs, and CableLabs is hosting Interoperability Events this year and next year to bring manufacturers together to help iron out the technology kinks.

We expect these features to become available to cable operators in the next year as they prepare their network to support low latency services.

LLD provides a cost-effective means of leveraging the existing hybrid fiber-coaxial (HFC) network to provide a high-performance network for latency-sensitive services. These services will help address customers’ requirements for many years into the future, maximizing the investments that cable operators have made in their networks. The cable industry is provisioning the network with substantial bandwidth and low latency to take another leap forward with its 10G networks.

For those attending the SCTE Cable-Tec Expo in New Orleans, Greg will be presenting the details of this technology on a SCTE panel “Low Latency DOCSIS: Current State and Future Vision”

Innovation

IPoC: A New Core Networking Protocol for 5G Networks

5G is the latest iteration of cellular network technology developed to meet the growing traffic demand for both smartphones and homes. With beamforming and frequency bands reaching millimeter waves, 5G promises many benefits:

- Higher speeds

- Lower latency

- The ability to connect many more devices

However, current de jure standards and protocols, designed for earlier technologies, have the potential to dilute these promises. To address the limitations of current networks, CableLabs developed the IP over CCN (IPoC) protocol, a compelling new solution to meet the new, more robust requirements of 5G.

Why a New Solution?

The primary goal of the fourth generation (4G or LTE) technology was access to the Internet, so the technology utilized IP networking, the packet routing technology historically and currently used in the Internet.

IP networking has been around since the mid-1970s and has served us remarkably well, but it isn’t without flaws. The purpose of the Internet Protocol is to allow a computer at one fixed location in the network to exchange information with another computer at a fixed location in the network. For mobile devices (that clearly aren’t at a fixed location) this has never been a great fit, and LTE technology had to develop complicated IP over IP tunneling mechanisms (the LTE Evolved Packet Core (EPC)) to enable mobility.

Furthermore, in the majority of cases, a mobile application wants to fetch specific data (say the text and images of a blog post) but doesn’t really care which computer it talks to in order to get it. As a result, to improve network efficiency and performance, network operators (both mobile and fixed) have implemented complex Content Distribution Networks in order to try to redirect the mobile application to the nearest server or cache that has the requested data.

In LTE-EPC, all of a user’s IP traffic is tunneled through a centralized choke point (or anchor) in the mobile operator’s core network, which eliminates the ability to serve data from a nearby cache. Also, as a mobile device moves in the network, the EPC needs to create new tunnels and tear down old ones in order to ensure that the user’s data reaches them.

These limitations are widely acknowledged by standards-setting groups. They are currently soliciting input to introduce new protocols that will pave the way for 5G to meet the demands of next-generation technologies, specifically:

- Improve the efficiency and performance of the network mobility plane, compared to today’s LTE standards,

- Support non-IP network protocols, of which Content Centric Networking is a leading candidate.

Benefits of Content Centric Networking

Content Centric Networking: A networking paradigm that emphasizes content by making it directly addressable and routable. Learn more here.

CCN offers several key advantages over IP networking:

- It employs “stateful forwarding” which elegantly and efficiently supports information retrieval by mobile client devices without the need for tunneling or a location registration protocol

- It addresses content directly rather than addressing end hosts, which means that it enables in-network caching, processing and intelligent packet forwarding, allowing it to excel in content retrieval optimization, allowing data to be easily retrieved from an on-path cache

- It supports a client device using multiple network attachments (e.g., radio links) simultaneously, providing greater reliability and performance.

- Its design meets the needs of large-data and IoT applications

For many new applications, CCN provides a much better fit for purpose than the Internet Protocol.

IP over CCN (IPoC): A New Way to Handle IP

In spite of the significant improvements Content Centric Networking offers over current IP networking, the reality is that all of today’s applications, both client and server, are built to use IP networking. We developed IPoC as the solution to this issue. IP over CCN (IPoC) protocol is a general-purpose tunneling protocol that enables delivery of IP traffic over a Content Centric Network (CCN) or a Named Data Network (NDN).

IPoC enables deployment of CCN as the core networking protocol for 5G, both for new, native CCN applications and as a mobility plane for existing IP applications, replacing the LTE-EPC. As a result, IPoC saves the IP investment and allows a full transition to the new CCN protocol.

With this approach:

- Native CCN applications reap the benefits of tunnel-free anchorless networking, along with the latency and efficiency gains that come from in-network caching.

- Existing IP-based applications can be supported with a mobility management solution that is simpler than the existing LTE-EPC. Gone are the special-purpose tunnel management functions that create and destroy tunnels as mobile devices move in the network.

- The need for network slicing to accommodate both IP and CCN and the complications and overhead entailed in running two core networks in parallel are eliminated.

IPoC Performance in Mobile Networks

With the assistance of two PhD students from Colorado State University, we developed simulation models and conducted performance and efficiency testing of the protocol in comparison to LTE-EPC. In our simulation study, we implemented the IPoC protocol using the Named Data Networking (NDN) simulator ndnSim (which implements a CCN-like semantic) and used mobile communication as the driving example, comparing IPoC-over-NDN protocol performance against GTP-over-IP. We found that the protocol overhead and performance impact of IPoC is minimal, which makes it suitable for immediate deployment. The report on this study includes links to the source code as well.

Want to Take a Closer Look?

IPoC can be best understood as a transition technology. Providing a shim layer and allowing CCN to act as a mobility plane for legacy IP applications, it accommodates the current protocol standards while opening the door for deployment of native CCN applications and the benefits they offer.

The 5G standardization project is seeking new mobility solutions for 5G, and we believe CCN and IPoC would be a great solution to address the needs. We have submitted a definition of the IPoC protocol as an Internet-Draft to the Internet Research Task Force (IRTF) Information Centric Networking Research Group. In addition, we have developed a proof-of-concept implementation of the IPoC protocol on Linux.

Interested in learning more? Subscribe to our blog and recieve updates on 5G by clicking below.

Networks

Re-Inventing the Internet

The Internet Protocol – IP. It has become practically synonymous with networking, and over the last 40 years the adoption of IP has radically changed the world economy and the way that people interact globally, with CableLabs and the cable industry being a major force in that adoption. The past 15+ years in particular have been marked by the transitioning of the significant majority of industries, services, and human interactions into versions that are mediated by the world wide web, itself built on the foundation of the Internet Protocol. As this transition has taken place, the way that we use the network has radically evolved, from a simple point-to-point (or end-to-end) model with static endpoints, into one of massively distributed computing and storage accessed almost entirely by a huge number of mobile and nomadic client devices (with content and virtualized services being deployed on demand wherever it is most advantageous).

Alongside this usage evolution, network engineers have evolved in the way that they build IP networks, constructing ever more complex systems to try to manage the flow of communication, and have even taken on a change of the IP protocol (from IPv4 to IPv6) in an attempt to solve its most pressing shortcoming, the size of the address space. However, it is becoming more apparent that the address space issue is not the only problem with IP, and that we may be nearing the day when a more fundamental re-invention is needed.

A New Approach to Networking

Information Centric Networking is an emerging networking approach that aims to address many of the shortcomings inherent in the existing Internet Protocol. The field of Information Centric Networking was sparked by work at Stanford University in 1999-2002, which proposed a radical re-thinking of the network stack and a fundamental change in the way information flows in the global data network. Since that time, a number of researchers have developed proposals for the operational model, semantics, and syntax of an Information Centric Network, and today, one technology appears to be leading the pack and to be poised for potential success. This approach to Information Centric Networking, being developed in parallel by two projects: Content-Centric Networking (CCN) and Named Data Networking (NDN), appears to be gaining mindshare in the research community and in industry, and promises to significantly improve network scalability and performance, and reduce cost over a network built on the Internet Protocol. CCN/NDN provides native, and elegant, support for client mobility, multipath connectivity, multicast delivery and in-network caching, many of which are critical for current and future networks, and all of which require inefficient and/or complex managed overlays when implemented in IP. Further, CCN/NDN provides a much richer addressing framework than that which exists in IP (which could eliminate significant sources of routing complexity), and it provides a fundamentally more secure communication model, even for in-the-clear communications.

By moving away from a "host-centric" view of networking functions, where the core protocol (IP) is entirely devoted to delivering data from one specific host to another, to a "content-centric" view, where content objects are identified and routed solely by the use of globally unique names, the CCN/NDN approach provides a more elegantly scalable, faster, and more efficient network infrastructure for the majority of traffic on the Internet today. To get a sense of how big a mind shift this is, consider this: in CCN/NDN devices don’t have addresses at all. A device can retrieve content by requesting it by name, without needing to have a way of identifying a server where that content is stored, or even identifying itself.

At CableLabs, we are experimenting with this new protocol and are deep into investigating the applications that might drive its adoption. Because CCN/NDN is built with mobility, privacy and efficient content distribution in mind from the beginning, we see synergies with the direction that cable networks are going. We see this as enabling a convergence of fixed networking, mobile networking and content distribution – a “Fixed-Mobile-Content Convergence”.

As IP is baked into the networking field (equipment, software stacks, applications, services, engineering knowledge, business models, even national policies), it may seem daunting to consider the use of a non-IP protocol. However, while IP has been a phenomenally successful networking protocol for the last 40 years, as technology and time inevitably marches on it is reasonable to believe that we won’t be utilizing it forever. And furthermore, while replacing IP with another protocol will certainly bring implementation challenges, it doesn’t follow that doing so necessarily means changing the way applications and users interact with the network. In other words, the web will still look and act like the web, but it will become more streamlined and efficient.

To be clear, CCN/NDN is not a mature protocol ready for immediate deployment. A number of R&D issues are still being worked in academic and industry research groups (including CableLabs), and implementations (both endpoint stacks and network gear) are still largely in the reference implementation or proof-of-concept stage. However, development work is active and confidence is high that the protocol will be ready for deployment in the next 3-5 years.

As part of this investigation, CableLabs has released a publication describing how an existing Content Distribution Network (CDN) evolves to one that leverages the benefits of CCN.

Greg White is a Distinguished Technologist at CableLabs.

DOCSIS

How DOCSIS 3.1 Reduces Latency with Active Queue Management

At CableLabs we sometimes think big picture, like unifying the worldwide PON standards, and sometimes we focus on little things that have big impacts.

In the world of cable modems a lot has been said about the ever-increasing demand for bandwidth, the rock-solid historical trend where broadband speeds go up by a factor of about 1.5 each year. But alongside the seemingly unassailable truth described by that trend is the nagging question: "Who needs a gigabit per second home broadband connection, and what would they use it for?" Are we approaching a saturation point, where more bits-per-second isn't what customers focus on? Just like no one pays much attention to CPU clock rates when they buy a new laptop anymore, and megapixel count isn't the selling point it once was for digital cameras.

It's clear that aggregate bandwidth demand is increasing, with more and more video content (at higher resolutions and greater color depths) being delivered, on-demand, over home broadband connections. DOCSIS 3.1 will deliver this bandwidth in spades. But, in terms of what directly impacts the user experience, what is increasingly getting attention is latency.

Packet Latency and Application Performance

Latency is a measure of the time it takes for individual data packets to traverse a network, from a tablet to a web server, for example. In some cases it is referred to as "round trip time," both because that's easier to measure, and because for a lot of applications, it’s what is most important.

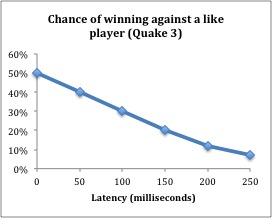

For network engineers, latency has long been considered important for specific applications. For example, it has been known since the earliest days of intercontinental telephone service that long round-trip times cause severe degradation to the conversational feeling of the connection. It’s similar for interactive games on the Internet, particularly ones that require quick reaction times, like first-person-shooters. Latency (gamers call it "lag" or "ping time") has a direct effect on a player's chance of winning.

Based on data from M. Bredel and M. Fidler, "A Measurement Study regarding Quality of Service and its Impact on Multiplayer Online Games", 2010 9th Annual Workshop on Network and Systems Support for Games (NetGames), 16-17 Nov. 2010.

But for general Internet usage, web browsing, e-commerce, social media, etc. the view has been that these things aren't sensitive to latency, at least at the scales that modern IP networks can provide. Does a user really care that much if their Web browsing traffic is delayed by a few hundred milliseconds? That's just the blink of an eye – literally. Surely this wouldn't be noticed, let alone be considered a problem. It turns out that it is a problem, since a typical webpage can take 10 to 20 round-trip-times to load. So, an eye-blink delay of 400ms in the network turns into an excruciating 8-second wait. That is a killer for an e-commerce site, and for a user's perception of the speed of their broadband connection.

And, it turns out that more bandwidth doesn't help. Upgrading to a "faster" connection (if by faster we mean more Mbps) will have almost zero impact on that sluggish experience. For a typical webpage, increasing the connection speed beyond about 6 Mbps will have almost no effect on page load time.

If Latency is Indeed Important, What Can We Do About It?

There is a component of latency that comes from the distance (in terms of network link miles) between a client and a server. Information currently travels at near the speed of light on network links, and, while some network researchers have bemoaned that "Everybody talks about the speed of light, but nobody ever does anything about it" (Joe Touch, USC-ISI), it seems that once we harness quantum entanglement we can call that one solved. Until that day comes, we have to rely on moving the server closer to the client by way of Web caches, content-delivery networks, and globally distributed data centers. This can reduce the round-trip-time by tens or hundreds of milliseconds.

Another component of latency comes from the time that packets spend sitting in intermediate devices along the path from the client to the server and back. Every intermediate device (such as a router, switch, cable modem, CMTS, mobile base station, DSLAM, etc.) serves an important function in getting the packet to its destination, and each one of them performs that function by examining the destination address on the packet, and then making a decision as to which direction to forward it. This process takes some time, at each network hop, while the packet waits for its turn to be processed. Reducing the number of network hops, and using efficient networking equipment can reduce the round-trip-time by tens of milliseconds.

But, there is a hidden, transient source of significant latency that has been largely ignored – packet buffering. Network equipment suppliers have realized that they can provide better throughput and packet-loss performance in their equipment if they include the capability of absorbing bursts of incoming packets, and then playing them out on an outgoing link. This capability can significantly improve the performance of large file transfers and other bulk transport applications, a figure of merit by which networking equipment is judged. In fact, the view has generally been that more buffering capability is better, since it further reduces the chance of having to discard an incoming packet due to having no place to put it.

The problem with this logic is that file transfers use the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) to control the flow of packets from the server to the client. TCP is designed to try to maximize its usage of the available network capacity. It does so by increasing its data rate up to the point that the network starts dropping packets. If network equipment implements larger and larger buffers to avoid dropping packets, and TCP by its very design won't stop increasing its data rate until it sees packet loss, the result is that the network has large buffers that are being kept full whenever a TCP flow is moving files, and packets have to sit and wait in a queue to be processed.

Buffering in the network devices at the head of the bottleneck link between the server and the client (in many cases this is the broadband access network link) have the most impact on latency. And, in fact, we see huge buffers supported by some of this equipment, with buffering delays of hundreds or thousands of milliseconds being reported in many cases, dwarfing the latency caused by other sources. But it is a transient problem. It only shows up when TCP bulk traffic is present. If you test the round-trip time of the network connection in the absence of such traffic, you would never see it. For example, if someone in the home is playing an online game or trying to make a Skype call, whenever another user in the home sends an email with an attachment, the game or Skype call will experience a glitch.

Is There a Solution to This Problem?

Can we have good throughput, low packet loss and low latency? At CableLabs, we have been researching a technology called Active Queue Management where the cable modem and CMTS will keep a close eye on how full their buffers are getting, and as soon as they detect that TCP is keeping the buffer full, they will drop just enough packets to send TCP the signal that it needs to slow down, so that more appropriate buffer levels can be maintained.

This technology shows such promise for radically improving the broadband user experience, that we've mandated it be included in DOCSIS 3.1 equipment (both cable modem and CMTS). We've also amended the DOCSIS 3.0 specification to strongly recommend that vendors add it to existing equipment (via firmware upgrade) if possible.

On the cable modem, we took it a step further and require that devices implement an Active Queue Management algorithm that we've specially designed to optimize performance over DOCSIS links. This algorithm is based on an approach developed by Cisco Systems, called "Proportional Integral Enhanced Active Queue Management" (or, more commonly known by its less tongue-tying acronym: PIE), and incorporates original ideas from CableLabs and several of our technology partners to improve its use in cable broadband networks.

By implementing Active Queue Management, cable networks will be able to reduce these transient buffering latencies by hundreds or thousands of milliseconds, which translates into massive reductions in page load times, and significant reductions in delays and glitches in interactive applications like video conferencing and online gaming, all while maintaining great throughput and low packet loss.

Active Queue Management: A little thing that can make a huge impact.

Greg White is a Principal Architect at CableLabs who researches ways to make the Internet faster for the end user. He hates waiting 8 seconds for pages to load.

For more information on Active Queue Management in DOCSIS, download the white paper.